Geometric planning for car-like vehicles

Mark Moll

For several vehicle models it is possible to compute the optimal (i.e., shortest) path between a start and end state. The two most commonly studied vehicle models are the Dubins car and the Reeds-Shepp car. Both are first-order models. The Dubins car’s controls are: go straight, turn left, and turn right. The Reeds-Shepp car has the same controls, but can also execute them in reverse. The optimal paths for these vehicles can be computed analytically and consist of 3 to 5 circle and straight-line segments. In OMPL we could model cars with a system of differential equations and use a control-based planner. For the Dubins and Reeds-Shepp cars, however, we simply use a geometric planner and plan in SE(2). Rather than straight-line interpolation between states, we’d like to use the appropriate optimal path in our local planner. This is done by creating two new state spaces, ompl::base::DubinsStateSpace and ompl::base::ReedsSheppStateSpace, that override the distance and interpolate member functions. The distance is redefined to be the length of the optimal path connecting two states.

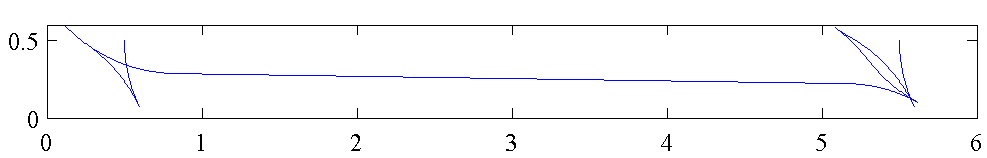

There is a demo program (demo_GeometricCarPlanning) that shows how to solve planning problems in this state space. Imagine a long corridor with the start and goal states of a Reeds-Shepp car at each end point, facing the wall. Normally, for a control based planner this could be a very challenging problem. With the Reeds-Shepp state space this is very easy and we get paths that looks like this:

(Note the extra zig-zag at the end; the paths are only optimal between sampled states, not globally optimal.)

The distance function is not a metric for Dubins cars, since it is not symmetric. With an optional flag you can create a DubinsStateSpace where distance is symmetrized (which essentially allows the car to instantaneously change direction when it reaches a sampled state). This is still not a metric, since it doesn’t satisfy the triangle inequality.

The computation of optimal paths is not optimized at all. For both Dubins and Reeds-Shepp cars all candidate solutions are computed and the shortest one is returned. There exist classification schemes that depending on the relative distance and orientation between two states can eliminate many of the candidate solutions. It may also be possible to use some form of memoization. The implementation of Dubins and Reeds-Shepp vehicles may be usable for other vehicle models. If someone wants to contribute code for the generalized solutions from Furtuna and Balkcom’s paper on Generalizing Dubins Curves: Minimum-time Sequences of Body-fixed Rotations and Translations in the Plane, that’d be much appreciated.

Finally, just because we can, we made some videos of the distances between a car at (0,0) and heading along the X-axis and all other possible poses. Each frame shows the distances for a particular heading at the endpoint. Black correspond to small distances and white corresponds to large distances.